Oklahoma State University Athletics

Moe Iba: A blast from the past

September 03, 2024 | Cowboy Basketball

This article was originally published in the Fall 2020 online edition of POSSE magazine.

During his 36 years as head basketball coach of the Aggies and Cowboys, Hall of Fame coach Henry Iba led two teams to NCAA titles, made four trips to the Final Four, won 14 Missouri Valley championships plus a Big Eight crown. The celebrated Iba also coached three U.S. Olympic squads. At the time of his 1970 retirement, Iba had posted 757 victories on his resume, the third-best total in history at the time.

"I had never heard of basketball lectures until I played for Mr. Iba in the Olympics," said former U.S. Senator, past presidential candidate and NBA star Bill Bradley. "But his lectures were as much about life as they were about basketball."

What would it be like to be the son of this legendary coach? More unnerving, perhaps, what would it be like to have your father as your legendary coach?

The year was 1939. Time magazine's man of the year was Russian leader Joseph Stalin. Yankee Lou Gehrig's streak of playing in 2,130 consecutive starts came to an end. The college craze was swallowing goldfish and Henry W. (Moe) Iba was born to Henry P. and Doyne Iba in Stillwater, Okla.

Shortly thereafter, an uncle hung the moniker Moe on the infant, after a popular comic strip baby that never grew.

It stuck.

Eighty-year-old Moe Iba looks at least 15 years younger than his chronological age. He played for his dad, then went on to coach college basketball for 32 seasons.

Moe's lifelong friend since grade school, Stan Ward, told me, "Moe deserves a story. Cowboy fans need to know more about him. I hope you do a good job."

So here goes.

MEETING MOE

I was a freshman basketball player at Oklahoma State during Moe's senior year. I'd see him on the rare occasion when the varsity practiced with us underlings, and they would work us over pretty good.

Moe's teammate, all-conference forward, Cecil Epperly, remembers those days. "We were just trying to toughen you guys up."

One 100-plus degree July evening in Gallagher Hall, several basketball players worked out. Sweat dripped off everyone. I shagged balls for Moe as he sank 113 consecutive free throws, then missed before drilling another 47.

Amazing. I'd never seen such a soft touch.

Fast forward some 58 years, and I'd probably seen Moe twice—both times at basketball reunions—and we only spoke briefly. This past September, Moe showed up at the annual reunion of former players.

I saw Moe across the court from me. He looked dapper in a dark pullover sweater, tailored slacks, and polished loafers. Possessing a full head of hair, which was mostly grey with specs of brown, his raspy voice reminded me of his dad's.

Approaching him, he smiled as we shook hands and exchanged small talk. I found Moe to be an easy person to talk with. Before we parted, he gave me the okay to write a story on him. I looked forward to it as it provided me an opportunity to get to know him better and, hopefully, the same for Cowboy fans.

STARTING IN STILLWATER

For Moe, growing up in Stillwater was the perfect place.

"Small college town, and I attended all the high school and college sporting events," he said. "As a young teenage boy, I could leave in the morning with some of my friends, spend the day playing ball or whatever, then return in the evening and nobody worried about us."

"Dad was a normal dad. He taught me to hunt and fish. Of course, being a coach, he was gone a lot. Mom instructed me on how to play golf and was there with me all the time. They were both excellent parents and taught me to be the best person I could be. I had a very good upbringing. Mom was probably the best female golfer in Stillwater, winning several state championships. She loved to play, and it was excellent exercise for her. Her father had been a U.S. congressman from Missouri for 18 years."

Moe's interest in basketball came at an early age.

"I can't say exactly when," he reflects, "because, at a young age, probably four or five, I would go to practices with Dad all the time. I played on my first town team when I was about six-years-old, and then on the 12-14 age group. Our Stillwater team won a state championship. All I wanted to do was shoot baskets."

"I don't think I was that good at baseball," Moe added. "And during football season, all I wanted to do was shoot the basketball, so that's what I did."

Moe became an all-state player and a high school All-American but broke his hand as the state playoffs began. Ironically, on that same high school squad was Epperly, Don Linsenmeyer, and Eddie Bunch, all of whom became stellar players for OSU.

Linsenmeyer was a fan of Moe Iba.

"He could shoot lights out with anyone," he said of his former teammate. "He was a terrific ball handler and passer, smart player, and a great teammate."

The lifelong relationship between Stan Ward and Moe began at Eugene Fields Elementary School in Stillwater.

"We played on the same little league teams. Moe was in my wedding. We always kept up with each other, and then one day we woke up and we were both 80! Neither one of us have a brother, but Moe is like a brother to me.

"Dedicated, at an early age, to become a great basketball player, Moe spent countless hours on the court shooting the ball. Moe also had excellent hand-eye coordination and could hit a baseball better than any of us.

"In high school, Moe would attend the OSU practice sessions and on occasion, played 'horse' against the varsity players. More often than not, he won. Too bad the three-point line wasn't in back in those days, because where Moe shot from.

"The only regret I have for Moe is that he never coached at OSU. He bled orange all the time he was here and had deep affections for the program."

As a youngster, Moe knew there was something special about his dad.

"I don't remember the national championship teams in 1945 and '46, but in 1949, when I was 10 years old, I listened on the radio to the NCAA finals when Kentucky beat us. I knew Dad was very successful. I saw how other coaches respected him for his innovations, coaching abilities, and because he was honest."

Moe, on high school Stillwater's Hall of Fame coach Martin "Red" Loper: "Red was great. I spent a lot of time talking basketball with him after I got out of high school. He was very knowledgeable."

Following Moe's senior year, TCU offered him a full scholarship, and he accepted.

"I was in Gallagher Hall working out for the upcoming all-state game when trainer Doc Johnson walked onto the court and asked me what I thought about coming to OSU," Moe said. "I told him, 'Of course I wanted to come.' That was the first time anyone had asked me. Back then a letter of intent wasn't binding, so I switched. Dad never said anything to me about it."

DAD

Moe Iba was bored by his freshman season.

"I felt it was a waste of time," he said. "We couldn't play on the varsity nor could we play any real games. Occasionally we got to scrimmage the varsity. Only thing besides practice that we could do was play intramural teams, which wasn't a lot of fun."

Beginning his sophomore year, disappointment engulfed Moe as he had knee surgery and had to redshirt. He didn't play in a single game, which was a bitter pill for Moe to swallow.

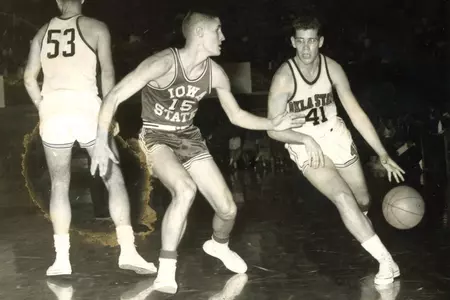

Finally, following 12 months of rehab and preparation for a return to the court, Moe saw action. As a part-time starter, he averaged just over five points a game, his high being 19 against Kansas State during a season he remembers as "losing a few more than we won."

As a junior starter, Moe averaged 11 points per game, scoring 21 against both K-State and Iowa State.

"Looking back, that was my best year," said Moe. "I stayed healthy, we won some games, and finished third in the conference."

Also, that season Moe connected on 92 percent of his free throws, including 11-for-11 against Colorado. Moe's season free throw percentage set a record that stood for 46 years—until 2017 when Phil Forte hit 95 percent of his attempts, breaking the OSU record and leading the NCAA in the process.

Readying themselves for Moe's final season, the Cowboys seemed poised for success. It appeared the Pokes would have four starters from Stillwater High. They called themselves the Four Amigos: Moe Iba; junior post player Eddie Bunch; junior Epperly, an absolute demon on the boards who would lead the conference the following season in rebounding; and sophomore Linsenmeyer, who could do it all and might have been the best player of the bunch.

But it was not to be. Moe and Linsenmeyer both went down with knee injuries. Linsenmeyer was just coming into his own and averaged 19 points per game his last two pre-injury outings. Moe played in 15 games, averaging 12.5 points.

Toward the end of the season, Moe didn't know if he could play, but after discussing it with Mr. Iba, decided to give it a try.

"There were about four games left: Kansas, Nebraska, K-State, and OU," Moe said with a smile, "and we won all four of them! I'm kind of proud of that fact."

K-State was ranked third in the nation at that time. Beating them was a huge deal, and Moe played a major role in those victories. The Nebraska encounter was a nail-biter. OSU trailed by a point with six ticks left and a jump ball on the Husker free-throw line. Epperly, a terrific leaper, tipped the ball to Moe who had a head of steam up as he raced toward midcourt. He caught the ball in stride and released it two steps before he reached half-court.

As a witness to the event, the ball seemed to float in slow motion, and then suddenly, the ball went in!

Pandemonium broke out with fans storming the court to embrace the victors.

"Yes, I remember that game," Moe says, with a grin.

"Thing is," Moe reflected, "I really didn't expect to play again. It's one of those things I look back on, and I'm glad I did it. If Don and I don't get hurt, we might have won a few more games."

The Cowboys finished 14-17 (7-7 in conference for a fourth-place finish). After great expectations, it turned into a disappointing season. But Moe was ready to get on with his life.

COACH MOE IBA

For as long as he could remember, Moe Iba wanted to a college basketball coach, just like his dad.

"Only thing about being the son of the coach," said Moe, "is that I wanted to be accepted by the coaches and the players, and I believe I was. What I got out of college basketball was a foundation to take with me into coaching. I learned so much from my dad—offense and defense, really all parts of the game. If things were going bad for me, I tried to recall what he would do."

"That next year, 1962, along with my wife Cindy (a former OSU cheerleader) and young sons Bret and Greg, we moved to El Paso, where I took a job as an assistant to Don Haskins." The school is now known as UTEP—back then it was called Texas Western.

"The only reason I got the job was Don had played for Dad," Moe said. "Being the only assistant coach, I coached the freshman team and assisted Don with the varsity, plus helped recruit. Don pretty much ran things as Dad did, except he applied more defensive pressure on their guards, so there wasn't a lot for me to learn."

"Don had been a great shooter in college, had terrific eye-hand coordination, was a good golfer, and would take your money on the pool table. I'm fortunate Don hired me. He was a great coach and a really, really good recruiter. He could charm the recruit, his mother, and whoever else might be in the room. It's remarkable how Don got all those kids down there. We had terrific players, players who could play today."

"Bobby Joe Hill, one of the quickest players I ever saw, drove Don crazy by dribbling and passing behind his back, but he was good at it. Don was constantly on him, raising hell with him. I was having dinner with Don, and he's complaining to me about Bobby Joe. Finally, I suggested to Don that he would either have to run Bobby Joe off or let him do what he was capable of doing. Don was quiet. Next practice he began to pull back some."

Fast forward three years to the 1965-66 season: UTEP won the national championship, beating Kentucky in the finals. A Hollywood movie, "Glory Road," was filmed, based on this event.

According to Moe, "Some UTEP fans felt our 1963 squad was better than our championship team. That team included Jim Barnes who went on to be the number one pick in the 1963 NBA draft. Also, "Glory Road" compresses everything into one year, when it actually took three. But overall, I thought they did a good job with the movie."

"We really didn't know what we had with that '66 team; but then we played No. 4 Iowa on the road and beat them by 40," he added. "We knew we were pretty special and began steamrolling. We only had two regular season games in which we had a chance of losing."

"Beating Adolph Rupp and Kentucky, was that a big deal? Not really. The movie had innuendos about racism since our team was black and Kentucky was white. We didn't see it that way. We just wanted to win a championship. I do think that game helped open doors for black athletes in the southeast."

THE HEAD COACH

Following the 1966 season, Moe Iba became the head coach at Memphis State.

"I thought I knew a lot, but found out I didn't," he said. "It was a mistake. I wasn't ready. Memphis had never had a black player and freshmen couldn't play. The first year, as an independent, we won 17 games and went to the NIT. Then we joined the Missouri Valley Conference, and I was able to recruit a few players. My last year there I recruited two that would eventually lead Memphis to the NCAA finals, losing to UCLA. But I lost my job because we didn't have good years in the conference."

Moe went on to take the freshman job at Nebraska and then became an assistant to Joe Cipriano at the school. When Cipriano got cancer in 1980, Moe became the head coach.

"Nebraska was my favorite job," Moe recalls. "We had good teams, went to three NITs back when only 32 teams got in the NCAAs, and my final season, 1986, we went to the NCAA Tournament, a place where Nebraska had never been."

"Unfortunately, I had a problem with a regent so I resigned."

Moe spent one year as an assistant coach at Drake University. Jim Killingsworth, a friend of Moe's and a former OSU head coach, retired at TCU and was instrumental in getting Moe that job.

"That was a good job," he said. "I enjoyed my time there, and we had four or five good teams. We played in the Southwest Conference, and if you didn't win your conference, you couldn't go to the NCAA, which we weren't going to do any time soon, so I decided to retire from college coaching."

Playing for Moe:

"The older I get, the more I appreciate Moe and what a super, genuine gentleman he was and is," said former Nebraska player Terry Novak. "I value his friendship. When he was coaching, he frequently yelled at me, but I knew it was to make me better.

"Today, Moe remains one of my best friends. I'd do anything for that guy. A few of us get together two or three times a year for golfing and fishing outings and we'll continue to do that for as long as Moe wants to do it.

"We don't really go out in the evenings, but I believe that he is impressed with our beer drinking abilities. Moe takes good care of himself, but when we're together he seems to enjoy the rest of us acting like clowns. He frequently refers to Stillwater as God's Country. I laugh and tell him that is a stretch.

"You probably have maybe four or five basketball coaches in your life from little league through college; I learned a lot about basketball from Moe. After Moe's dad retired, he would come up for a week or so to watch us practice. Marvelous man, Mr. Iba. He would talk to anyone, whether you were the star or the last guy on the end of the bench. Moe has those same characteristics. I see where he gets them."

AND NOW

"I think you know I lost my wife Cindy a while back," Moe said. "We married during college. She was a wonderful mom and wife. She took care of the kids, enjoyed sports, supported me well while I was coaching and was always there for me. Her passing was a great loss."

Moe retired from basketball but didn't really retire from basketball.

"For seven years I was an NBA scout, working at different times for Detroit and Toronto," he said. "It was something I enjoyed, but lots of travel. I've liked having free time, and it's enabled me to get closer to my three sons (Bret, Greg, and Blake), which has been good for me."

"My health enables me to play golf, take fishing trips, travel and do whatever I want to do. Plus, I have a circle of great friends I enjoy."

"After I'd been out for several years, Haskins, also retired, asked me if I missed it. I told him no and didn't see how some guys coach into their mid-70s and he agreed."

"Someone asked me if I ever shoot free throws anymore. I haven't shot any in a long time with one exception. A few years ago, I was with a group on a fishing trip in Alaska and we were staying at a lodge. Outside was a basketball goal and a ball. I went outside, picked up the ball and shot it. It came up about four feet short and I've never picked up another ball," Moe laughed.

Moe still keeps an eye on Stillwater and the Oklahoma State basketball program.

"Something else I'd like to add to your story," he concluded. "I realize Dad accomplished a lot of good for OSU. He earned Oklahoma State a lot of respect, fame, glory and notoriety. At the same time, the university has done a wonderful job recognizing and appreciating my father."

"But I want the fans to know how much OSU meant to him. It was everything. He used to say, 'Family comes first, then OSU and last basketball.' He appreciated and loved everyone and everything about Oklahoma State. That was his whole life. Also, I loved OSU as well. Still do."

So, Cowboy fans, here is your Moe Iba story: From OSU royalty, someone who bleeds orange, a basketball player extraordinaire, long-time coach. I found him to be sincere, humble, easy to communicate with, a quality individual, and a family man—a delightful blast from the past.

During his 36 years as head basketball coach of the Aggies and Cowboys, Hall of Fame coach Henry Iba led two teams to NCAA titles, made four trips to the Final Four, won 14 Missouri Valley championships plus a Big Eight crown. The celebrated Iba also coached three U.S. Olympic squads. At the time of his 1970 retirement, Iba had posted 757 victories on his resume, the third-best total in history at the time.

"I had never heard of basketball lectures until I played for Mr. Iba in the Olympics," said former U.S. Senator, past presidential candidate and NBA star Bill Bradley. "But his lectures were as much about life as they were about basketball."

What would it be like to be the son of this legendary coach? More unnerving, perhaps, what would it be like to have your father as your legendary coach?

The year was 1939. Time magazine's man of the year was Russian leader Joseph Stalin. Yankee Lou Gehrig's streak of playing in 2,130 consecutive starts came to an end. The college craze was swallowing goldfish and Henry W. (Moe) Iba was born to Henry P. and Doyne Iba in Stillwater, Okla.

Shortly thereafter, an uncle hung the moniker Moe on the infant, after a popular comic strip baby that never grew.

It stuck.

Eighty-year-old Moe Iba looks at least 15 years younger than his chronological age. He played for his dad, then went on to coach college basketball for 32 seasons.

Moe's lifelong friend since grade school, Stan Ward, told me, "Moe deserves a story. Cowboy fans need to know more about him. I hope you do a good job."

So here goes.

MEETING MOE

I was a freshman basketball player at Oklahoma State during Moe's senior year. I'd see him on the rare occasion when the varsity practiced with us underlings, and they would work us over pretty good.

Moe's teammate, all-conference forward, Cecil Epperly, remembers those days. "We were just trying to toughen you guys up."

One 100-plus degree July evening in Gallagher Hall, several basketball players worked out. Sweat dripped off everyone. I shagged balls for Moe as he sank 113 consecutive free throws, then missed before drilling another 47.

Amazing. I'd never seen such a soft touch.

Fast forward some 58 years, and I'd probably seen Moe twice—both times at basketball reunions—and we only spoke briefly. This past September, Moe showed up at the annual reunion of former players.

I saw Moe across the court from me. He looked dapper in a dark pullover sweater, tailored slacks, and polished loafers. Possessing a full head of hair, which was mostly grey with specs of brown, his raspy voice reminded me of his dad's.

Approaching him, he smiled as we shook hands and exchanged small talk. I found Moe to be an easy person to talk with. Before we parted, he gave me the okay to write a story on him. I looked forward to it as it provided me an opportunity to get to know him better and, hopefully, the same for Cowboy fans.

STARTING IN STILLWATER

For Moe, growing up in Stillwater was the perfect place.

"Small college town, and I attended all the high school and college sporting events," he said. "As a young teenage boy, I could leave in the morning with some of my friends, spend the day playing ball or whatever, then return in the evening and nobody worried about us."

"Dad was a normal dad. He taught me to hunt and fish. Of course, being a coach, he was gone a lot. Mom instructed me on how to play golf and was there with me all the time. They were both excellent parents and taught me to be the best person I could be. I had a very good upbringing. Mom was probably the best female golfer in Stillwater, winning several state championships. She loved to play, and it was excellent exercise for her. Her father had been a U.S. congressman from Missouri for 18 years."

Moe's interest in basketball came at an early age.

"I can't say exactly when," he reflects, "because, at a young age, probably four or five, I would go to practices with Dad all the time. I played on my first town team when I was about six-years-old, and then on the 12-14 age group. Our Stillwater team won a state championship. All I wanted to do was shoot baskets."

"I don't think I was that good at baseball," Moe added. "And during football season, all I wanted to do was shoot the basketball, so that's what I did."

Moe became an all-state player and a high school All-American but broke his hand as the state playoffs began. Ironically, on that same high school squad was Epperly, Don Linsenmeyer, and Eddie Bunch, all of whom became stellar players for OSU.

Linsenmeyer was a fan of Moe Iba.

"He could shoot lights out with anyone," he said of his former teammate. "He was a terrific ball handler and passer, smart player, and a great teammate."

The lifelong relationship between Stan Ward and Moe began at Eugene Fields Elementary School in Stillwater.

"We played on the same little league teams. Moe was in my wedding. We always kept up with each other, and then one day we woke up and we were both 80! Neither one of us have a brother, but Moe is like a brother to me.

"Dedicated, at an early age, to become a great basketball player, Moe spent countless hours on the court shooting the ball. Moe also had excellent hand-eye coordination and could hit a baseball better than any of us.

"In high school, Moe would attend the OSU practice sessions and on occasion, played 'horse' against the varsity players. More often than not, he won. Too bad the three-point line wasn't in back in those days, because where Moe shot from.

"The only regret I have for Moe is that he never coached at OSU. He bled orange all the time he was here and had deep affections for the program."

As a youngster, Moe knew there was something special about his dad.

"I don't remember the national championship teams in 1945 and '46, but in 1949, when I was 10 years old, I listened on the radio to the NCAA finals when Kentucky beat us. I knew Dad was very successful. I saw how other coaches respected him for his innovations, coaching abilities, and because he was honest."

Moe, on high school Stillwater's Hall of Fame coach Martin "Red" Loper: "Red was great. I spent a lot of time talking basketball with him after I got out of high school. He was very knowledgeable."

Following Moe's senior year, TCU offered him a full scholarship, and he accepted.

"I was in Gallagher Hall working out for the upcoming all-state game when trainer Doc Johnson walked onto the court and asked me what I thought about coming to OSU," Moe said. "I told him, 'Of course I wanted to come.' That was the first time anyone had asked me. Back then a letter of intent wasn't binding, so I switched. Dad never said anything to me about it."

DAD

Moe Iba was bored by his freshman season.

"I felt it was a waste of time," he said. "We couldn't play on the varsity nor could we play any real games. Occasionally we got to scrimmage the varsity. Only thing besides practice that we could do was play intramural teams, which wasn't a lot of fun."

Beginning his sophomore year, disappointment engulfed Moe as he had knee surgery and had to redshirt. He didn't play in a single game, which was a bitter pill for Moe to swallow.

Finally, following 12 months of rehab and preparation for a return to the court, Moe saw action. As a part-time starter, he averaged just over five points a game, his high being 19 against Kansas State during a season he remembers as "losing a few more than we won."

As a junior starter, Moe averaged 11 points per game, scoring 21 against both K-State and Iowa State.

"Looking back, that was my best year," said Moe. "I stayed healthy, we won some games, and finished third in the conference."

Also, that season Moe connected on 92 percent of his free throws, including 11-for-11 against Colorado. Moe's season free throw percentage set a record that stood for 46 years—until 2017 when Phil Forte hit 95 percent of his attempts, breaking the OSU record and leading the NCAA in the process.

Readying themselves for Moe's final season, the Cowboys seemed poised for success. It appeared the Pokes would have four starters from Stillwater High. They called themselves the Four Amigos: Moe Iba; junior post player Eddie Bunch; junior Epperly, an absolute demon on the boards who would lead the conference the following season in rebounding; and sophomore Linsenmeyer, who could do it all and might have been the best player of the bunch.

But it was not to be. Moe and Linsenmeyer both went down with knee injuries. Linsenmeyer was just coming into his own and averaged 19 points per game his last two pre-injury outings. Moe played in 15 games, averaging 12.5 points.

Toward the end of the season, Moe didn't know if he could play, but after discussing it with Mr. Iba, decided to give it a try.

"There were about four games left: Kansas, Nebraska, K-State, and OU," Moe said with a smile, "and we won all four of them! I'm kind of proud of that fact."

K-State was ranked third in the nation at that time. Beating them was a huge deal, and Moe played a major role in those victories. The Nebraska encounter was a nail-biter. OSU trailed by a point with six ticks left and a jump ball on the Husker free-throw line. Epperly, a terrific leaper, tipped the ball to Moe who had a head of steam up as he raced toward midcourt. He caught the ball in stride and released it two steps before he reached half-court.

As a witness to the event, the ball seemed to float in slow motion, and then suddenly, the ball went in!

Pandemonium broke out with fans storming the court to embrace the victors.

"Yes, I remember that game," Moe says, with a grin.

"Thing is," Moe reflected, "I really didn't expect to play again. It's one of those things I look back on, and I'm glad I did it. If Don and I don't get hurt, we might have won a few more games."

The Cowboys finished 14-17 (7-7 in conference for a fourth-place finish). After great expectations, it turned into a disappointing season. But Moe was ready to get on with his life.

COACH MOE IBA

For as long as he could remember, Moe Iba wanted to a college basketball coach, just like his dad.

"Only thing about being the son of the coach," said Moe, "is that I wanted to be accepted by the coaches and the players, and I believe I was. What I got out of college basketball was a foundation to take with me into coaching. I learned so much from my dad—offense and defense, really all parts of the game. If things were going bad for me, I tried to recall what he would do."

"That next year, 1962, along with my wife Cindy (a former OSU cheerleader) and young sons Bret and Greg, we moved to El Paso, where I took a job as an assistant to Don Haskins." The school is now known as UTEP—back then it was called Texas Western.

"The only reason I got the job was Don had played for Dad," Moe said. "Being the only assistant coach, I coached the freshman team and assisted Don with the varsity, plus helped recruit. Don pretty much ran things as Dad did, except he applied more defensive pressure on their guards, so there wasn't a lot for me to learn."

"Don had been a great shooter in college, had terrific eye-hand coordination, was a good golfer, and would take your money on the pool table. I'm fortunate Don hired me. He was a great coach and a really, really good recruiter. He could charm the recruit, his mother, and whoever else might be in the room. It's remarkable how Don got all those kids down there. We had terrific players, players who could play today."

"Bobby Joe Hill, one of the quickest players I ever saw, drove Don crazy by dribbling and passing behind his back, but he was good at it. Don was constantly on him, raising hell with him. I was having dinner with Don, and he's complaining to me about Bobby Joe. Finally, I suggested to Don that he would either have to run Bobby Joe off or let him do what he was capable of doing. Don was quiet. Next practice he began to pull back some."

Fast forward three years to the 1965-66 season: UTEP won the national championship, beating Kentucky in the finals. A Hollywood movie, "Glory Road," was filmed, based on this event.

According to Moe, "Some UTEP fans felt our 1963 squad was better than our championship team. That team included Jim Barnes who went on to be the number one pick in the 1963 NBA draft. Also, "Glory Road" compresses everything into one year, when it actually took three. But overall, I thought they did a good job with the movie."

"We really didn't know what we had with that '66 team; but then we played No. 4 Iowa on the road and beat them by 40," he added. "We knew we were pretty special and began steamrolling. We only had two regular season games in which we had a chance of losing."

"Beating Adolph Rupp and Kentucky, was that a big deal? Not really. The movie had innuendos about racism since our team was black and Kentucky was white. We didn't see it that way. We just wanted to win a championship. I do think that game helped open doors for black athletes in the southeast."

THE HEAD COACH

Following the 1966 season, Moe Iba became the head coach at Memphis State.

"I thought I knew a lot, but found out I didn't," he said. "It was a mistake. I wasn't ready. Memphis had never had a black player and freshmen couldn't play. The first year, as an independent, we won 17 games and went to the NIT. Then we joined the Missouri Valley Conference, and I was able to recruit a few players. My last year there I recruited two that would eventually lead Memphis to the NCAA finals, losing to UCLA. But I lost my job because we didn't have good years in the conference."

Moe went on to take the freshman job at Nebraska and then became an assistant to Joe Cipriano at the school. When Cipriano got cancer in 1980, Moe became the head coach.

"Nebraska was my favorite job," Moe recalls. "We had good teams, went to three NITs back when only 32 teams got in the NCAAs, and my final season, 1986, we went to the NCAA Tournament, a place where Nebraska had never been."

"Unfortunately, I had a problem with a regent so I resigned."

Moe spent one year as an assistant coach at Drake University. Jim Killingsworth, a friend of Moe's and a former OSU head coach, retired at TCU and was instrumental in getting Moe that job.

"That was a good job," he said. "I enjoyed my time there, and we had four or five good teams. We played in the Southwest Conference, and if you didn't win your conference, you couldn't go to the NCAA, which we weren't going to do any time soon, so I decided to retire from college coaching."

Playing for Moe:

"The older I get, the more I appreciate Moe and what a super, genuine gentleman he was and is," said former Nebraska player Terry Novak. "I value his friendship. When he was coaching, he frequently yelled at me, but I knew it was to make me better.

"Today, Moe remains one of my best friends. I'd do anything for that guy. A few of us get together two or three times a year for golfing and fishing outings and we'll continue to do that for as long as Moe wants to do it.

"We don't really go out in the evenings, but I believe that he is impressed with our beer drinking abilities. Moe takes good care of himself, but when we're together he seems to enjoy the rest of us acting like clowns. He frequently refers to Stillwater as God's Country. I laugh and tell him that is a stretch.

"You probably have maybe four or five basketball coaches in your life from little league through college; I learned a lot about basketball from Moe. After Moe's dad retired, he would come up for a week or so to watch us practice. Marvelous man, Mr. Iba. He would talk to anyone, whether you were the star or the last guy on the end of the bench. Moe has those same characteristics. I see where he gets them."

AND NOW

"I think you know I lost my wife Cindy a while back," Moe said. "We married during college. She was a wonderful mom and wife. She took care of the kids, enjoyed sports, supported me well while I was coaching and was always there for me. Her passing was a great loss."

Moe retired from basketball but didn't really retire from basketball.

"For seven years I was an NBA scout, working at different times for Detroit and Toronto," he said. "It was something I enjoyed, but lots of travel. I've liked having free time, and it's enabled me to get closer to my three sons (Bret, Greg, and Blake), which has been good for me."

"My health enables me to play golf, take fishing trips, travel and do whatever I want to do. Plus, I have a circle of great friends I enjoy."

"After I'd been out for several years, Haskins, also retired, asked me if I missed it. I told him no and didn't see how some guys coach into their mid-70s and he agreed."

"Someone asked me if I ever shoot free throws anymore. I haven't shot any in a long time with one exception. A few years ago, I was with a group on a fishing trip in Alaska and we were staying at a lodge. Outside was a basketball goal and a ball. I went outside, picked up the ball and shot it. It came up about four feet short and I've never picked up another ball," Moe laughed.

Moe still keeps an eye on Stillwater and the Oklahoma State basketball program.

"Something else I'd like to add to your story," he concluded. "I realize Dad accomplished a lot of good for OSU. He earned Oklahoma State a lot of respect, fame, glory and notoriety. At the same time, the university has done a wonderful job recognizing and appreciating my father."

"But I want the fans to know how much OSU meant to him. It was everything. He used to say, 'Family comes first, then OSU and last basketball.' He appreciated and loved everyone and everything about Oklahoma State. That was his whole life. Also, I loved OSU as well. Still do."

So, Cowboy fans, here is your Moe Iba story: From OSU royalty, someone who bleeds orange, a basketball player extraordinaire, long-time coach. I found him to be sincere, humble, easy to communicate with, a quality individual, and a family man—a delightful blast from the past.

Cowboy Basketball Media Availability | Oklahoma State Postgame vs. Iowa State (01-24-2026)

Saturday, January 24

Sergio Vega PIN vs Missouri - Oklahoma State Wrestling (01/23/26)

Saturday, January 24

Jax Forrest TECH FALL vs Missouri - Oklahoma State Wrestling (01/23/26)

Saturday, January 24

Cowgirl Basketball Media Availability | Oklahoma State Postgame vs. Iowa State (01-18-2026)

Sunday, January 18